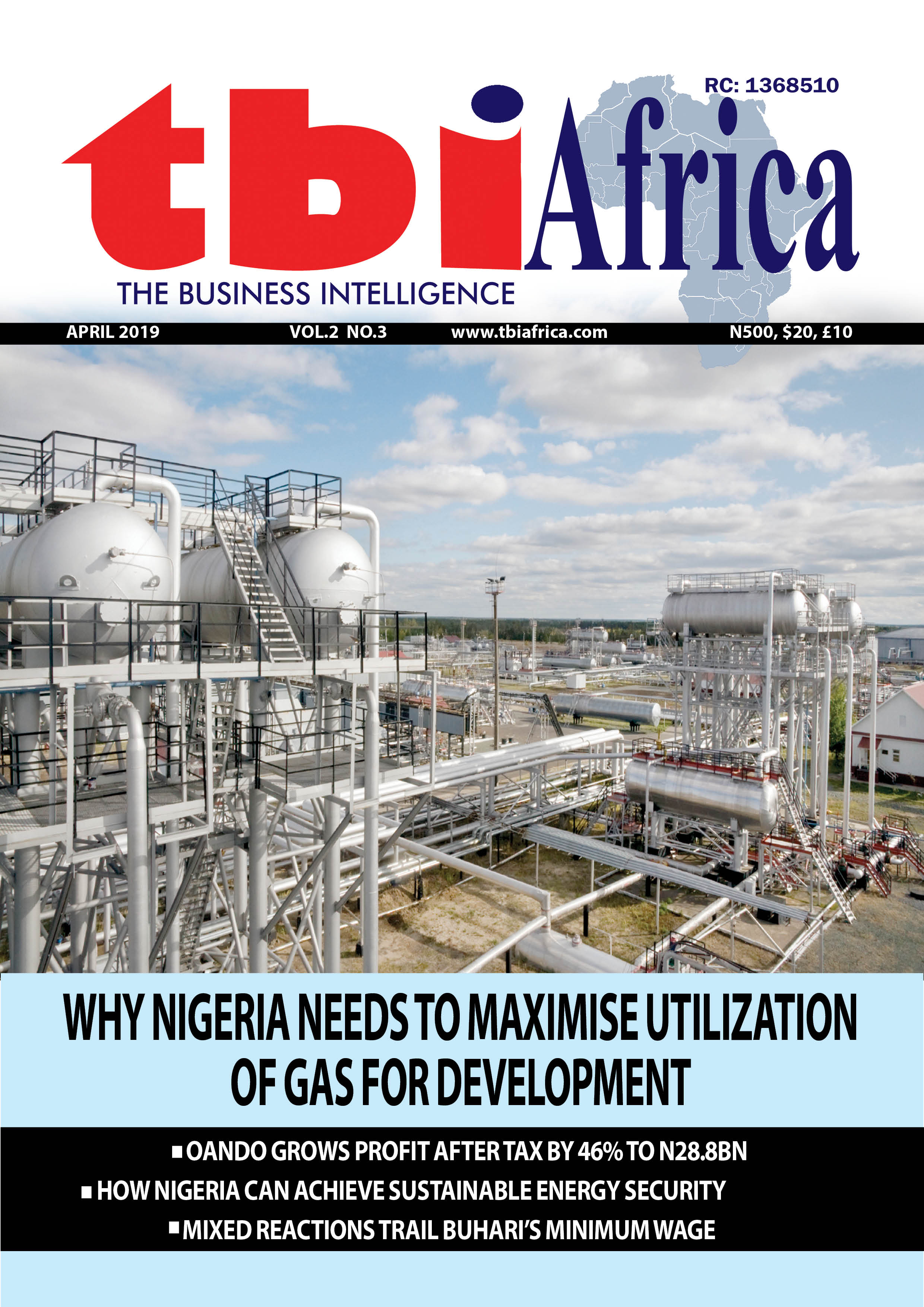

Contrary to projections that oil demand in many African countries will witness substantial recovery this year, at least from what it was before the outbreak of coronavirus pandemic, latest reports show that low output from refineries on the continent has raised the importation of fuel to new heights. This is a disturbing development that makes the rehabilitation of moribund refineries and the building of new ones, very imperative. For Nigeria, this is even more urgent.

CITAC, a renowned African-focused oil consultancy firm, in a recent report, noted that fuel imports into the African continent remains very high, as requirements by West African countries, including Nigeria, are expected to trigger spike in regional demand. This is a warning signal for African governments to weigh in on fuel needs. Indeed, compared with other regions such as Europe where oil demand is unlikely to reach pre-pandemic level at least till early next year, statistics indicate that oil consumption through import will likely exceed forecast this year, and much more by the third quarter(Q3) of 2022.

For Nigeria, this holds some negative economic implications unless the Dangote refinery comes on stream later this year or early in 2023. Already, the $1.5billion rehabilitation of the Port Harcourt refinery has reportedly commenced, but doubts still persist that it is going to quickly reduce the present level of fuel import into the country.

However, the worry for now is that total refining output in Africa remains abysmally low. This is because many refineries remain either shut down, or in a sorry state of disrepair. Those still functioning are running at below capacity. For example, in the case of Nigeria, the four refineries in Port Harcourt, Warri and Kaduna, did not process any crude oil since the last quarter of 2020. The four refineries have a combined capacity of 445,000 barrel per day(bpd). But more than N19billion was spent on the refineries for maintenance by the Nigeria National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC).

The four refineries, according to available data, recorded a total loss of N177.21billion from July 2019 to January 2021. This is despite not refining any crude oil within the period. This low refining capacity has resulted in an alarming increase in fuel import that has eaten deep into the country’s external reserves.

The situation is not different in other African countries with high fuel consumption. For instance, South Africa’s refinery output reportedly fell by 28 per cent last year as almost all its refineries were shut in April and May 2020 due to the COVID-19 lockdown. Consequently, South Africa imported 296,000 bpd of refined products, according to estimates from Kpler, a data intelligence outfit. This is the highest in almost a decade, and it compares with 198,000 bpd and 178,000 bpd in 2019 and 2020, respectively. The case is not different from that of Cameroun, where its main refinery, Limber refinery, suffered a fire disaster in May 2019, prompting immediate closure. Also, in Ghana, the Tema refinery has been operating intermittently as a result of operational difficulties.

The situation will lead to rise in fuel imports. Expectedly, Africa’s oil demand will reach a new high of 4.94 million bpd by the end of this year. It was 4.37 million bpd in 2019 and 4.50 million bpd last year.

The situation may likely push Nigeria to continue to import fuel with high sulphur content or ‘dirty fuel’ to meet up local demand. This will make it to lose the battle against the importation of dirty fuel into the country before the 2021 deadline. Besides, the reliance on imported petroleum products in the country will make it increasingly difficult for more investments in the oil sector, while there will be shortfall in funds for other developmental projects. With the importation of dirty fuel, millions of Nigerians will be exposed to some diseases, such as asthma, chronic bronchitis and lung disease.

We enjoin Nigeria and other African countries to develop local capacity to refine crude oil for local consumption and for export instead of depending so much on imported fuel. Local refining of crude oil will enable them maximise the use of other useful by-products of crude oil, especially bitumen used for road construction and others used in pharmaceutical and textile industries.

Let the concerned African countries embark on building new refineries while existing ones should be maintained to function optimally. Therefore, we call on all those given licences to build new refineries in the country to hasten action without further delay.