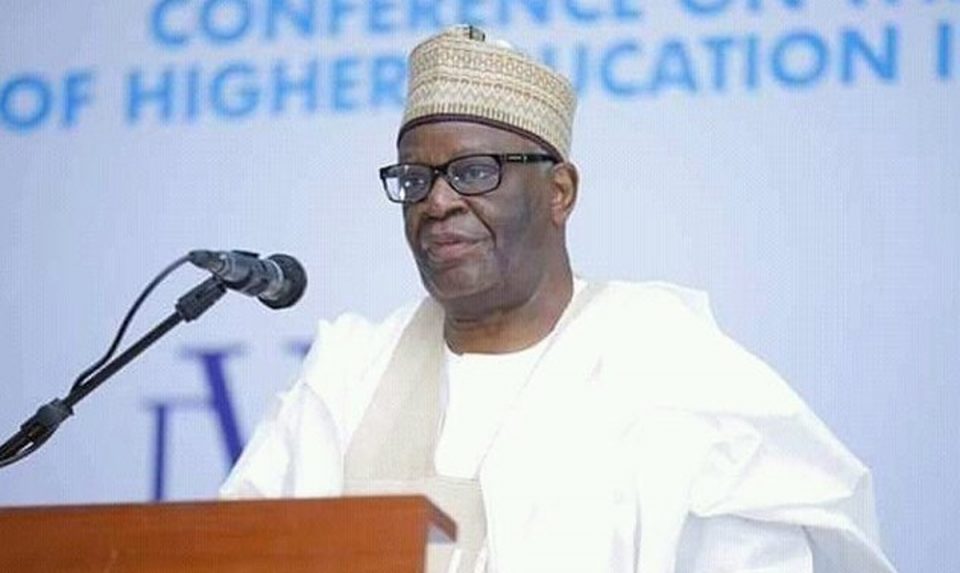

In 2015, Ibrahim Agboola Gambari, an economist and professor of international studies, was in the race to become newly elected President Muhammadu Buhari’s chief of staff. He missed the appointment narrowly. So he is no stranger to the president’s inner circle. Five years later, and 75 years of age, he has clinched the very demanding and contentious job of serving as the president’s clearing house, the Chief of Staff. One or two days before the appointment was announced, many analysts and commentators spoke out about the eminent professor, attesting to his character or lack of it, hoping perhaps the president would change his mind. He didn’t. Predictably, a loud and raucous controversy has broken out about the suitability of Prof Gambari for the job.

It hardly matters what anyone thinks now. The professor will occupy the office in the years to come, whether he is suitable or not. In all likelihood, he will stay in that office till the end of the Buhari presidency. Given his age, it will, however, likely be the last visible national appointment he will hold. He knows or senses this, and he will predictably give it his best shot, regardless of whether he or anyone thinks the office is essentially a demotion or promotion from his previous national and international assignments. As a tribute to his predecessor in that office, the late and somewhat controversial Abba Kyari, the office of the chief of staff has in the past few years become a hugely visible and influential one.

No one knows, not even the professor himself, whether he will project the office as influentially, spookily and controversially as Mr Kyari, but he has served notice, at least, that he will deploy the office with the same inscrutable anonymity his predecessor idiosyncratically and deliberately managed. Unlike Mr Kyari, however, whatever the professor does will be viewed from the cracked prism of the style and achievements of his predecessor. Worse, Prof. Gambari will not be starting on a clean slate like Mr Kyari, whose work was not assessed with regard to any other occupant of that sensitive office. There will always be the spectral shadow of the famous ‘benchmark’ referred to by Mamman Daura in his tribute to Mr kyari, against which he swore other chiefs of staff would be judged. Following hard on the heels of the late presidential aide, who was deemed to have raised the status of that office to dizzying heights, Prof Gambari should expect to be mercilessly and relentlessly dissected.

In short, as the president’s chief of staff, the eminent professor will labour under the crushing weights of his predecessor’s accomplishments as well as under his own foibles, many of which have been copiously discussed on various platforms in recent days, including the more sedate traditional media and the stupendously irreverent social media. If the professor manages to do his job well and comes out of the hullaballoo fairly unscathed, he will have proved himself nimble of feet as he is widely regarded as intellectually versatile. It is not clear why the president eventually settled for Mr Kyari in 2015, for the credentials of Prof Gambari were more intimidating; but in five years, it is sufficient for the public to note that the president had grown so fond of his late aide that he considered him nonpareil, the “very best of us”, as he elegantly gushed. It is a tough act to follow. How does one exceed or best the very best?

The presidential superlatives with which Mr Kyari was clothed at his death a few weeks ago was thought to be incomparable until his mentor and nephew to the president, Mr Daura, described the departed chief of staff as the benchmark by which future occupants of that office would be judged. Between the president’s superlatives and Mr Daura’s fulsomeness, it is hard to see anyone surviving the pressures exerted by the president’s hammer and Mr Daura’s anvil. Mr Kyari was not only intelligent, as the many tributes to him have indicated, his self-abnegation, language fluency and compatibility with the president, intellect, and master at balancing various interests, were critical both to his survival and his ascendancy. It will be futile for Prof Gambari to attempt to equal or rival the manners and work ethic of a predecessor who expired at 67. At 75, he should not try it, partly because the minds of the president and Mr Daura, and perhaps many other members of the so-called cabal that had and still have the ear of the president, are pretty much made up about their deceased protégé.

Expectations will be high. Many analysts, not to say presidential staff, will hope Prof Gambari will hit the ground running, and obviously running mostly in their directions. But the professor will need many weeks, regardless of his famed intellect, to find his feet and adjust to the demands of an office that has just witnessed the most radical and breathless transformation ever. The office of the chief of staff was imbued with presidential powers by President Buhari himself, a lower office where paradoxically and unconstitutionally the buck, yes, including military buck, stopped in Mr Kyari’s time. There were reasons for this, chief among which was the fact that the president was hobbled by both his fragile health and the extraordinary fact that the demands of a modern presidency, especially in a deeply fractured and heterogeneous society, were simply beyond the president’s ken.

It remains to be seen whether the power imbuement the office enjoyed was personal to Mr Kyari or temporarily institutional. If it was personal, will Prof Gambari enjoy the same access and confidence of the president? If it was to the office, could there be a few individuals who had endured the anomalous ways of Mr Kyari and would be unwilling to further tolerate the paradoxes that surrounded the former dispensation without making a pitch for the balkanisation of such humongous powers? Undoubtedly, there will be almost full devolution of powers to the office of the chief of staff. What is not clear is the shape of that devolution with regard to the new occupant of that very public office. The power play will manifest in the months ahead, once the new man gets into his stride.

The second weight under which Prof Gambari will labour in performing his duties is even more indisputable. It concerns the dismissive way many of his critics have summed his politics, character and style. Mr Kyari mounted the stool without much baggage, with little anyone could say about his person or politics beforehand; the eminent professor is mounting the stool with so much baggage, so much ill will, and so much contaminated politics. He has been described with saccharine prose by a few political heavy weights and friends of many years standing as an exemplary person and diplomat; but mostly, he has been excoriated by those whose trajectories crossed his, and many who had watched and suffered from what they describe as his appalling politics, indeed his galling realpolitik. To this last group, the professor will never be able to put a foot right.

Those who describe the professor’s appointment as fitting and deserved came to their conclusion partly because of his huge intellect, his impressive resume as a lecturer and high-profile diplomat, and his stamina in staying with the Buhari crowd for decades. It is inconceivable that such a resume would not have a positive spin off on the presidency. He is believed in the president’s circle, and perhaps beyond, to be a meticulous administrator with a lot of persuasive and winsome skills, a decisive person who would probably end the paralysis that dogged the work of his constantly edgy predecessor, a skilled negotiator who could help the president salve the wounds inflicted by opponents and critics, and a dependable loyalist who has said or done nothing to subvert or weaken the hegemonism that suffuses the Buhari presidency.

In contrast, Prof Gambari’s critics, armed with facts and figures, have been scathing and unsparing. They accuse him of being an apologist of dictatorship, having in the past wholeheartedly served some of Nigeria’s worst tyrants. They point at his dismissive characterisation of the environmental activist and writer, Ken Saro-Wiwa, who was extra-judicially murdered by the Sani Abacha military government, noting that it struck at the heart of the professor’s love for dictatorship, not to say his indescribable sense of justice. They also accuse him of celebrating the annulment of the June 12, 1993 presidential election, and wonder how as chief of staff to an elected president he could reconcile the instincts that are certain to be at war within him. They see him as someone who is fundamentally and poorly disposed to democracy, despite his long service in the diplomatic field, particularly in the United Nations. But there is nothing they accuse him of that the president is not guilty of. In fact, both he and the president share the same sentiments about democracy, about Gen Abacha, and about law and order, with which they have an uneasy but coarse relationship. Activists and civil society groups may object to Prof Gambari’s other credentials, but to the president and all who participated in enthroning the new chief of staff, the appointee is a perfect fit.

While the professor can talk his way glibly out of the thicket he had knowingly or ambitiously danced his way into, it is much harder for him to escape the damning accusation of being Machiavellian during his rise to the top. His critics give incontrovertible examples of his lack of principles: how he destroyed others to climb to the top, how he manifested a peculiar dislike for the Yoruba people within the context of national struggle for power, and his love for intrigues, perfidy and deceit. He is unlikely to be tempted to respond to these accusations. He will hide behind the cloak of the culture of his new office — which requires it to be seen and not heard — to deflect the damning allegations against his person and beliefs. Indeed, it is useless trying to deny these allegations. Few question their veracity. And the president, in all probability, does not care. But having being appointed, and knowing his deficiencies, let him come to terms with them, with his history and with his morality. Rather than excuse them, let him resolve to be a better man than he had been in the past 74 years, if he can try.

His predecessor, as he must have known, was the bete noire of the Buhari presidency, to whom was attributed all the insularity, lawlessness, ethnic prejudice, and general paralysis of that government. Prof Gambari is thought to be a tad better. Let him prove that he is. The president may gradually devolve powers to him as the months grind on; the country must, however, hope he will have the broadmindedness to deploy it for the greater good of the country. He is an ideological hegemonist, not a cultural hegemonist, unlike the president who is widely criticised for being both. In the next three years or so, the professor will traverse the corridors of power, and will discover the immenseness of the power that inheres in the Nigerian presidency, power the president has been unable to inclusively channel for the good of the country. But let the professor tread carefully, not inebriated by the power of that office, but sobered by it. Mr Kyari disguised his fixation with power, showing different sides to those with whom he related over the years, friends and family alike. But Mr Kyari’s friends and those who know him well insist he was not as destitute of character as his successor, whom some of them don’t like.

Curiously, however, some optimists hope that the coming of Prof Gambari to the corridors of immense power may bode well for the Buhari presidency which many critics had written off. It is not clear what the basis of that optimism is. But having served President Buhari in the 1980s as external affairs minister, and having loved the people and ideas the president seemed superficially enamoured of, it is fairly certain that both the professor and the president are birds of identical plumage, and would neither rock the national boat severely nor introduce the needed radical reforms that war against their hybrid conservatism. The professor will make some impact no doubt, and he will do it in the near term, but the public will discover that the erudite professor’s weaknesses will be reinforced by the president’s failings, and his strengths amplified by the president’s absenteeism. A powerful chief of staff office is a recent construct made possible by the president’s instinctive and ideological lacunae. That state of things cannot last. A knowledgeable and determined president will quickly reduce the office to its prior administrative foundations rather than tolerate it wielding undue influence, let alone contemplate the nonsense about one chief of staff or another making his time in office the benchmark for future chiefs of staff.

Prof Gambari is sensible enough to know that there is a limit to what good can be done with that office in a cultural and political milieu that stifles innovation, entrenches conservatism if not reaction, and promotes hidden interests over national interest. He knows how well he must try to balance competing interests round the country, and perhaps in the ruling party itself, and help a distant president manage an economy that could yet go into a tailspin. In the next one or two years, activities geared towards political transition would also begin. The president will be at the centre of it all, and by implication, his chief of staff also. If the professor can ensure that the attention of the president remains undivided and does not wander in the direction of those who gratify or exploit his prejudices; if the professor can think more expansively than his critics thought him capable of; if despite the communication/language problem he is certain to have with the president, he can still manage to steer his principal in the direction of all that is noble and inspiring about the presidency, perhaps this government can be redeemed. But nothing is guaranteed. Despite all criticisms, a blank cheque is now open before the president and his chief of staff. Let them write what is true and noble on it; and let them cash it at the right time.- The Nation